The Cross over Europe

Viewed from the outside, Europe stands out as a group of nations attached to democracy and human rights, and as a cultural zone with specific characteristics.

Looking from the inside, ‘we Europeans’ are much more aware of the mosaic of ethnic origins, languages, national and regional histories, political traditions, cultures, and lifestyles. Many of us are strongly attached to our particular identity, feeling ‘European’ only in a secondary or an accessory way.

At the same time, there are many connections between the peoples of Europe which are characteristic not just of that country but of the region to which they belong. When it comes to ethnic origins, we are a mixed rabble indeed. Incessant people movements in the past and migration today are complicating the picture. Tensions between the modern nation state and ethnic minorities are a recurrent phenomenon.

But when it comes to our many languages, there is some kind of a pattern. They are Latin in the south-east, Germanic in the north-east and Slavic in the east – with some exceptional cases here and there.

I would suggest that the cross provides us with a suitable symbol and a key. As we draw an imaginative cross over Europe, we become aware of four major parts.

North versus South

Alongside language, the geographic situation has determined culture. This includes climate, natural resources, arable land, commercial routes, and access to ports. The divide between the Mediterranean world and the Northern regions has a lot to do with climate and vegetation, which influence the agriculture, food patterns, lifestyle and traditions of a given society. The colder the climate, the harder one must work to survive and make living conditions more pleasant.

Another consequence of climate: families in the north live more indoors, in the south more outdoors. People drink wine in the south, beer in the north.

At the time of the Roman Empire, the natural north-south division largely coincided with the border between the ‘civilised’ peoples linked together by a Hellenistic-Roman culture, and the ‘uncivilised’ world of the Barbarians. In time the Roman Empire declined while the Barbarians adopted the (Christian) religion of their former foes. Gradually, the north-south divide lost its significance. But traces remained.

Even today, the Latin and Greek zones around the Mediterranean have distinct characteristics, as compared to the north. To mention just one example: in the south extended family structures are more important than any other social structure. Parents help their children with financial aid much longer than they generally do in northern countries.

It is a matter of interpretation where the north ends and the south begins. Belgium for instance has been called the most northern part of Latin Europe while people in northern France point out that the Latin mentality is only found in the southern part of their country. But wherever you draw the line, there is a difference between north and south. The Mediterranean world has a ‘feel’ of its own.

West versus East

Then there is the divide between West and East, going back to the old division between the western and the eastern Roman Empire. After the Empire was Christianised, the division continued between the Catholic Latin West and the Orthodox Greek East.

During the Middle-Ages, the peoples to the north and the east were evangelised by Catholics and Orthodox respectively, so the division line spread as well. Germanic and some Slavic peoples were incorporated in the Catholic realm, and most Slavic peoples into the Orthodox realm. As a result, the dividing line went right up to the northern outskirts of the continent, separating Scandinavia and the Baltic from Russia.

As the West developed global trade routes and colonial empires, the East seemed to lag behind. For a long time their elites were orientated towards France and Germany

Different interactions with Christianity

Christianity is a major, if not the main common denominator in the history of European peoples. At the same time it has also shaped their cultural diversity, more than anything else.

Again, there is a pattern in all this diversity, which strikingly largely overlaps with the linguistic pattern. South-west or ‘Latin’ Europe has almost exclusively been dominated by Roman Catholicism. North-west Europe with its Nordic and Germanic languages came largely under the influence of Protestantism while maintaining important Roman Catholic minorities. Slavic Europe was dominated by Roman Catholicism in the western part and by Orthodoxy further to the east, but Protestantism remained a marginal influence.

Finally, there is the south-eastern part Europe that seems to belong neither to East nor West. It is difficult to mark its frontier; it is even more difficult to give it a name. In the nineteenth century, the name ‘Balkan’ came to be used, denoting a region of incessant strife. Indeed, this is an area of tension, because it represents a mosaic of different ethnic origins, language groups, and religions. This is the only part of Europe where Islam has maintained a continual presence till the present day (Bosnia, Albania, and Kosovo). And we should not forget that Istanbul, ancient Constantinople, is a Muslim metropolis on European soil.

A socio-cultural cross

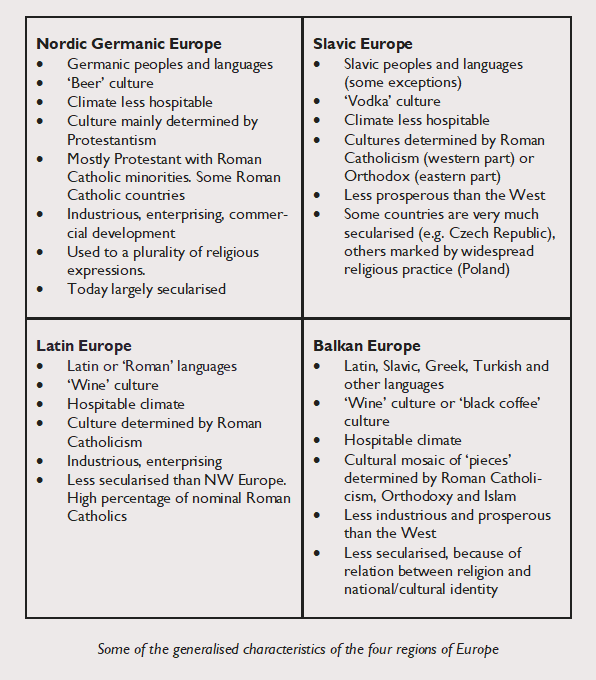

When we combine the geographical, linguistic, and religious zones, we can identify a ‘cross’, dividing Europe into four major socio-cultural ‘quarters.’

The ‘borders’ between these zones are abstractions of a more complex reality. But as one travels across Europe, at some point, travellers will realise that they have entered into another world, another kind of Europe.

Of course, this ‘cross’ does not visualise the religious and ethnic minorities spread all over Europe: Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, adherents of new religious movements. Nor does it bring out the increasing percentage of non-religious people.

Secularisation is taking place all over Europe, but it takes different forms in different zones. First, people who are not affiliated with any religious institution. We see this notably in Protestant and ex-communist countries, with peaks in the Netherlands, the eastern Germany and the Czech Republic.

Secondly, the non-practicing nominal members of Christian churches. This phenomenon is most widespread in traditionally Roman Catholic countries.

As to the ‘line’ between east and west, it seems to be moving eastwards as the EU expands to the east. Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, Hungarians, Czech and Poles like to consider themselves as being part of West. In their mind, the ‘East’ is Russia, Belarus, and the Ukraine.

Russian leaders often oppose their ‘Eurasian’ culture to the ‘American influenced culture of ‘Western’ Europe. Ukrainians themselves are divided to which side they belong, and this is the undercurrent of the troubles that rip their country. Some would even exclude the Russians from the European civilisation altogether. Meanwhile, Orthodox Church leaders insist that Russia and its neighbours are the inheritors of Byzantine Europe, standing in continuity with the Christianised Roman Empire, and therefore part of the ‘house of Europe’.

Understand resemblances and differences at a regional level

This cross over Europe is a generalisation, and a tentative one. We do not pretend to have analysed in depth the various aspects of these zones. Further research is necessary to refine and modify it. We have used a number of variables, but to check our provisional conclusions and refine the picture, other variables should be added, such as individual versus state initiative, tolerance of religious diversity in general and of Islam in particular, of the attitude towards authority.

Despite its provisional state, this cross clarifies why some national and regional cultures have more in common with each other than with others. It also helps workers in intercultural mission to understand that cultural dividing lines do not always correspond to national borders.

An interesting question for Evangelicals involved in mission in Europe is where and how does Evangelicalism fit into the picture?

How receptive is the population in each socio-cultural zone to the Evangelical expression of Christian faith, with its emphasis on conversion, personal relation with God and individual responsibility?

How do they relate to Evangelical forms of church life, with its ‘low liturgy’ and its emphasis on participating in and contributing to the witness of the Gospel?

For example, it appears that a population with a Protestant background (northern Europe) is generally more receptive than a population with a traditional Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox background.

Is there perhaps a distance between the church model generally used by Evangelicals, and the socio-cultural context of these zones. And if so, what are the implications for how Evangelicals practice mission in Europe today?

Evert van de Poll is a Dutch evangelical theologian, minister and former editor. He is presently a Baptist pastor in south France (Toulouse) and is university professor at the Evangelical Theological Faculty (ETF) in Heverlee, Leuven, Belgium.