Secularism and Islam in Europe

The same year that Charles Taylor published A Secular Age (2007), Philip Jenkins also wrote about the interface between religion and secular society in his book God’s Continent: Christianity, Islam, and Europe’s Religious Crisis. Jenkins explores the relationship between secular Europe, the historical Christian faith and Islam, and asks what form of Islam is likely to develop over time in Europe.

Will European Muslims reinforce their identity and stand apart as an increasingly strident and distinct Islamic community in Europe? Or is Islam likely to follow the path of Christianity and (in his view) become a ‘deeply secularised faith which has little by way of orthodoxy, preaches no morality and that conflicts with secular assumptions and does not try to impose its views in the ‘real world’?

While Jenkins rejects the idea of Islam becoming ‘deeply secularised,’ stating that ‘Western observers are over-optimistic if they believe that the alternative to Wahhabi fanaticism is a pallid liberal Islam, akin to American mainline churches’ (p.272), he does conjecture that ‘the long-term pressures are likely to create an ever more adaptable form of faith that can cope with social change without compromising basic beliefs’ (p.287).

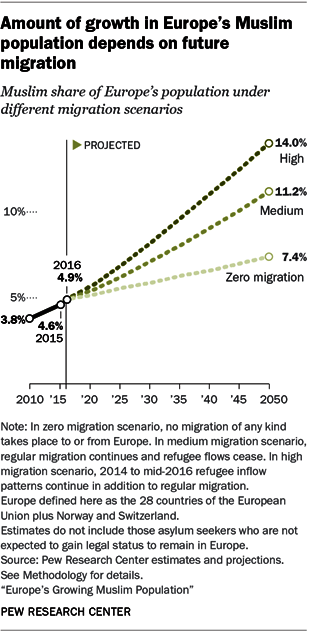

Twelve years later, the population of Muslims in Europe continues to grow – from an estimated 3.8% in 2010, to 4.9% in 2016. The recent Pew Center report on the Muslim population in Europe outlined three scenarios of migration which could influence the potential numbers of Muslims. If no further migration takes place, and growth only occurs through natural increase, it is likely that by 2050, 7.4% of Europe’s population will identify as Muslim. As it is very likely further immigration will happen, the actual proportion of the population is predicted to be between 11% and 14% overall.

Why is this significant when talking about secular culture? The Pew report also projects which individual countries are expected to see the most growth in their Muslim population: France, the UK, Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands, precisely those countries which we found to be at the very top of our Index of Secularity back in 2010 (See Vista Issue 3, October 2010). If the most secular countries are the ones with the highest percentage Muslim population, will this lead to increasing conflicts between Muslim immigrants and the host country?

Secular thought assumes the separation of religion and the state. If the activity of the state is public – for example the ‘public sector’ is shorthand in the UK for government-run organisations – then religious belief becomes a more private affair. Part of the ongoing clash between secular society and Islam is the philosophical difference regarding where religious activity should happen within the private-public spectrum.

For many Christians in secular Europe, who have adapted to the secular-sacred divide, faith has become largely a private affair despite calls for it to become more visible within the ‘public square’. Devotion to Islam, however, calls for a more public display – for example some may choose to wear the hijab, requiring prayer spaces in the workplace, or only eating halal food, which sits uncomfortably with societies where the public display of faith is not the cultural norm.

“Part of the ongoing clash between secular society and Islam is the philosophical difference regarding where religious activity should happen within the private-public spectrum.”

As with all religions, there is a spectrum of belief and practice, from ultra conservative or fundamentalist, to more liberal forms. Conservative Islam is identified in Europe, among other things, by burka-wearing women, and the desire for sharia law to be accepted by all. For a small minority, it also means their belief in jihad spills over into acts of terrorism against unbelievers.

At the other end of the spectrum are two movements which could be seen as actually taking Islam towards a non-religious agnostic, or secular, stance. The ‘One Law for All’ movement (onelawforall.org.uk) is particularly focused on marriage law and rights for women, and opposes giving space to sharia, stating that religious courts are ‘discriminatory and unjust’ and ‘work against rather than for human rights.’ Speaking at a 2018 conference organised by the movement, prominent activist Maryam Namazie asserted ‘the urgency of secularism as a minimum precondition for women’s and minority rights’. (onelawforall.org.uk/a-landmark-conference-for-universal-rights-and-secularism-and-against-fascism).

The second, the Council of Ex-Muslims, stresses the importance of universally held values, and the right for people to choose to leave Islam. The UK branch held two ‘coming out’ parties in 2018, where ex-Muslims were given ‘apostasy certificates’ and the opportunity to celebrate the loss of their faith rather than feel ashamed. (See www.ex-muslim.org.uk/cemb-partners for a list of where the Council is active).

Sociologist Nilüfer Göle appears to bridge the gap between the extremes of the religious-secular divide. In her most recent book The Daily Lives of Muslims: Islam and Public Confrontation in Contemporary Europe (2017), Göle explores some of the controversies that have arisen over issues such as public prayers, sharia laws, building mosques or wearing headscarves. She suggests that the fact that Muslims are more publicly visible – which causes discomfort to secularists – is actually a sign of their ‘growing participation in European daily life’. An example of the Europeanisation of Islam is given in the changing architecture of mosques, which are becoming more ‘hybrid’ rather than imitating traditional styles.

Most Muslims, she states, are satisfied with the secular nature of European society, and a ‘slow and invisible form of personal Islamic law is being constructed and adapted to European ‘secular’ laws’. An example of this is that the definition of halal is changing from the original Arab version, and a more European version which is ‘understood as permission, a lawful extension into new areas of life and pleasure that Muslims seek to enjoy. Halal certification makes these areas compatible with Islamic prescriptions…. [and] enables European Muslims to penetrate and so appropriate secular realms of life and pleasure.’

While this sounds a very positive step towards realising Jenkins’ prediction of Islam becoming a ‘more adaptable form of faith that can cope with social change without compromising basic beliefs’, Western governments appear to have a much narrower view on the meaning of ‘halal’. On 1 January this year, Belgium became the sixth country in Europe to ban killing animals without stunning them first rather than maintaining an exception for religious groups to the EU regulation that an animal must be stunned before being killed. For some, the argument is more about marginalising ‘certain groups’ who use halal meat, than animal welfare.

A decade after God’s Continent’s publication, the debate of the place of Islam in Europe continues. In any conversation, both parties need to listen to the other as otherwise the participants end up shouting over each other or talking at cross-purposes. In the conversation between Islam and secular Europe, this is a very real danger.

But it is also an opportunity for us to have a conversation – with both parties – as people who understand the times we live in and can also bring God’s perspective to bear.

Jo Appleton

References

Jenkins, P. (2007) God's Continent: Christianity, Islam, and Europe's Religious Crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pew (2017) ‘Europe’s Growing Muslim Population’ [online] www.pewforum.org/

2017/11/29/europes-growing-muslim-population [Accessed 5 January 2019].

Memory, J. (2010) ‘Measuring Secularity in Europe,’ Vista 3, October 2010, pp.5-6.

Göle, N. (2017) The Daily Lives of Muslims: Islam and Public Confrontation in Contemporary Europe, London: Zed Books.

Schreuer, M. (2019) ‘Belgium Bans Religious Slaughtering Practices, Drawing Praise and Protest’. New York Times 5 January 2019 [online] www.nytimes.com/

2019/01/05/world/europe/belgium-ban-jewish-muslim-animal-slaughter.html [Accessed 10 January 2019].