Lucena and Borrow – The Bible in Spain and Beyond

History is full of extraordinary coincidences. It is well known that Cervantes and Shakespeare, without question the most important figures of Spanish and English literature, died just a few days apart in April 1616. This brief article traces the lives of Lorenzo Lucena and George Borrow who, though little known, made significant contributions to the translation and distribution of the Spanish Bible during the 19th Century, and whose lives also have striking points of connection, even though there is no evidence they actually met each other.

Lorenzo Lucena Pedrosa was born in Aguilar de la Frontera, a small town in the province of Cordoba, Spain, on 25th March 1807. He became a priest of the Roman Catholic Church, then lecturer in theology and vice-rector of St Pelagius’ College, the local diocesan seminary.

Borrow was born just a few years earlier in East Dereham, Norfolk, England on 5th July 1803. A talented linguist, as a young man Borrow was contracted by the British and Foreign Bible Society to go to St Petersburg, Russia, to supervise the translation of the Bible into Manchu. After two years in Russia Borrow returned to Britain and shortly afterwards was sent to Spain with the charge of arranging the printing and distribution of the Bible in Spain.

On 6th January 1836 George Borrow crossed the frontier between Portugal and Spain en route to Madrid. Just two days later and unbeknown to Borrow, Lorenzo Lucena resigned from his post at the seminary declaring himself protestant and fled to Gibraltar.

Borrow arrived in Madrid at the end of January 1836 and immediately sought governmental permission to reprint but without notes the Catholic New Testament translated to Spanish from the Vulgate by Padre Scio some decades earlier. At the time Spain was in the throes of a civil war but nevertheless Borrow waited patiently for an audience with Prime Minister Mendizabal. The Prime Minister refused him permission for the printing but Borrow himself recalled Mendizabal’s words:

“What a strange infatuation is this which drives you over lands and waters with Bibles in your hands. My good sir, it is not Bibles we want, but rather guns and gunpowder, to put the rebels down with, and above all, money, that we may pay the troops; whenever you come with these three things you shall have a hearty welcome, if not, we really can dispense with your visits, however great the honour.”

Meanwhile in Gibraltar, Lucena had been licensed as an Anglican priest for the Spanish-speaking population, and had been commissioned by the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) to revise the text of another translation of the Vulgate by Catholic bishop Torres Amat.

The fall of Mendizabal’s government shortly afterwards allowed Borrow to begin publishing and distributing his Spanish New Testaments. Ever since his time in Russia Borrow had always been fascinated with the Roma and on arrival in Spain had fallen in with them during his first weeks. He learnt something of their language, enough at least to attempt a translation of Luke’s gospel into Caló, the Roma dialect of Spain´s gypsies, which was published in 1837. Borrow stayed in Spain for the best part of five years and on returning to Britain wrote up the story of his travels as “The Bible in Spain”, his most successful literary work.

In 1849 Lucena left Gibraltar for Liverpool where he spent ten years as a missioner to seamen as well as continuing to translate works on behalf of the Anglican church and teaching Spanish at a local school. Then in 1858 Lucena was invited to become the first Teacher of Spanish at the Taylorian Institution of the University of Oxford, a post he held until he died. And it was during his time in Oxford that Lucena made his most significant contribution to Bible translation and engagement.

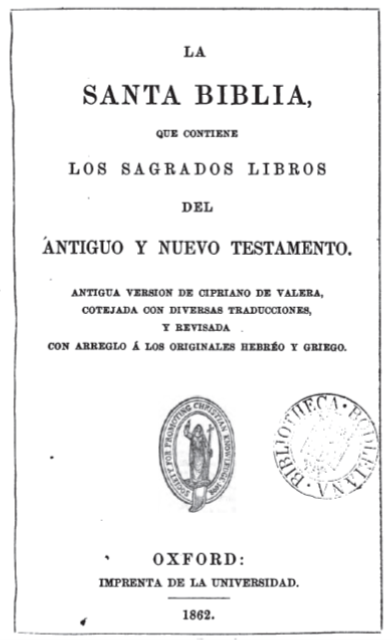

Sometime earlier the SPCK had approached Lucena to ask him to undertake a complete revision of the Bible translated from the original languages by protestant Spanish exiles Reina and Valera during the late 16th Century. Others had tried to do this but, when it was finally published in 1862, such was the quality of Lucena’s work that the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS), the Scottish Bible Society and the Trinitarian Bible Society all agreed to adopt Lucena’s revision and publish it as their own.

In 1909 when the BFBS and the American Bible Society collaborated in the publication of a new edition, it remained largely a retouching of Lucena revision. The millions of Reina Valera Bibles distributed throughout the Spanish speaking-world in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, largely in the revision undertaken by Lucena, have ensured that to this day the Reina Valera is the standard Bible used by most Spanish speaking protestants.

Though they lived most of their latter lives in the south of England there is nothing to suggest that Borrow and Lucena ever met. But together they arguably made the most significant 19th Century contributions to Spanish Bible translation and engagement. And like Shakespeare and Cervantes, they too were united even in death, as they were buried within one month of each other in July and August 1881.

The tens of millions of Spanish-speaking protestants today owe these two forgotten heroes of Bible translation and engagement a huge debt of gratitude.

Jim Memory

References

Borrow, G., The Bible in Spain, first published by John Murray 1843, http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/415

Edwards, J., Lorenzo Lucena (1807-1881), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, OUP 2015, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/98259

Fraser, A., George Borrow (1803-1881), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, OUP 2015, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/2918

Memory, J., “Lorenzo Lucena Pedrosa (1807-1881) Recuperando una figura señera de la Segunda Reforma Española”, Anales de Historia Contemporanea, Universidad de Murcia, 17, 2001, pp.213-226 http://revistas.um.es/analeshc/article/view/56341