More religious or more secular? Migrant religiosity encountering European secularity

Are migrants in Europe likely to be more secular or more religious than European-born nationals? That question recurs frequently and has become a central research focus for a growing number of smaller scale research projects with migrants and refugees. Most studies tend to suggest that migrants are generally more religious than national-born Europeans and that for some at least, the fact of relocating to, or being resettled in, a new country can be a catalyst in a change of religious affiliation and identity. This is most obviously seen in the anecdotal evidence of migrants and refugees from Islamic nations of the middle-east who have arrived in Europe and undergone conversion to Christian faith, commonly of a Pentecostal or evangelical form.

Frustratingly, there is relatively little data that reliably informs a pan-European picture of migrant faith or religious identity, affiliation, and practice. Happily, the 2017 versions of the European Values Survey (EVS) and the World Values Survey (WVS) allow some tentative comparisons to be made between migrants and non-migrants. Moreover, these two surveys capture responses from 34 countries of Europe. Across the sample of interviewees, 6.2% reported that they were an immigrant and not born in the country. Out of the 127,118 Europeans surveyed for the EVS and the WVS together, 7,839 declared themselves to be born outside the country. Whilst this sample size is small and certainly under-representative of the migrant populations of the countries in question, it is possible to point to religious affiliation, practice, and identity, even down to the level of migrants and denominational belonging.

“there is relatively little data that reliably informs a pan-European picture of migrant faith or religious identity, affiliation, and practice”

This latter fact is likely to be given close attention over the next few years as the EVS and WVS data undergoes further analysis. Our initial analysis here points to the potential within EVS-WVS data for further careful exploration and use by the churches and mission agencies of Europe. In addition to reporting the denominational belonging, we also attempt to compare migrant and non-migrant practices such as religious service attendance, and personal prayer. Furthermore, it is also possible to compare the professed beliefs of migrants with those of non-migrants.

The presentation here is limited to a pan-European overview; at national level the under-representation of migrants surveyed and the consequently small sample sizes for migrants’ religious practices and beliefs makes national analysis problematic in the absence of supporting data from other sources. Nevertheless, this is a promising start and bodes well for the future (1).

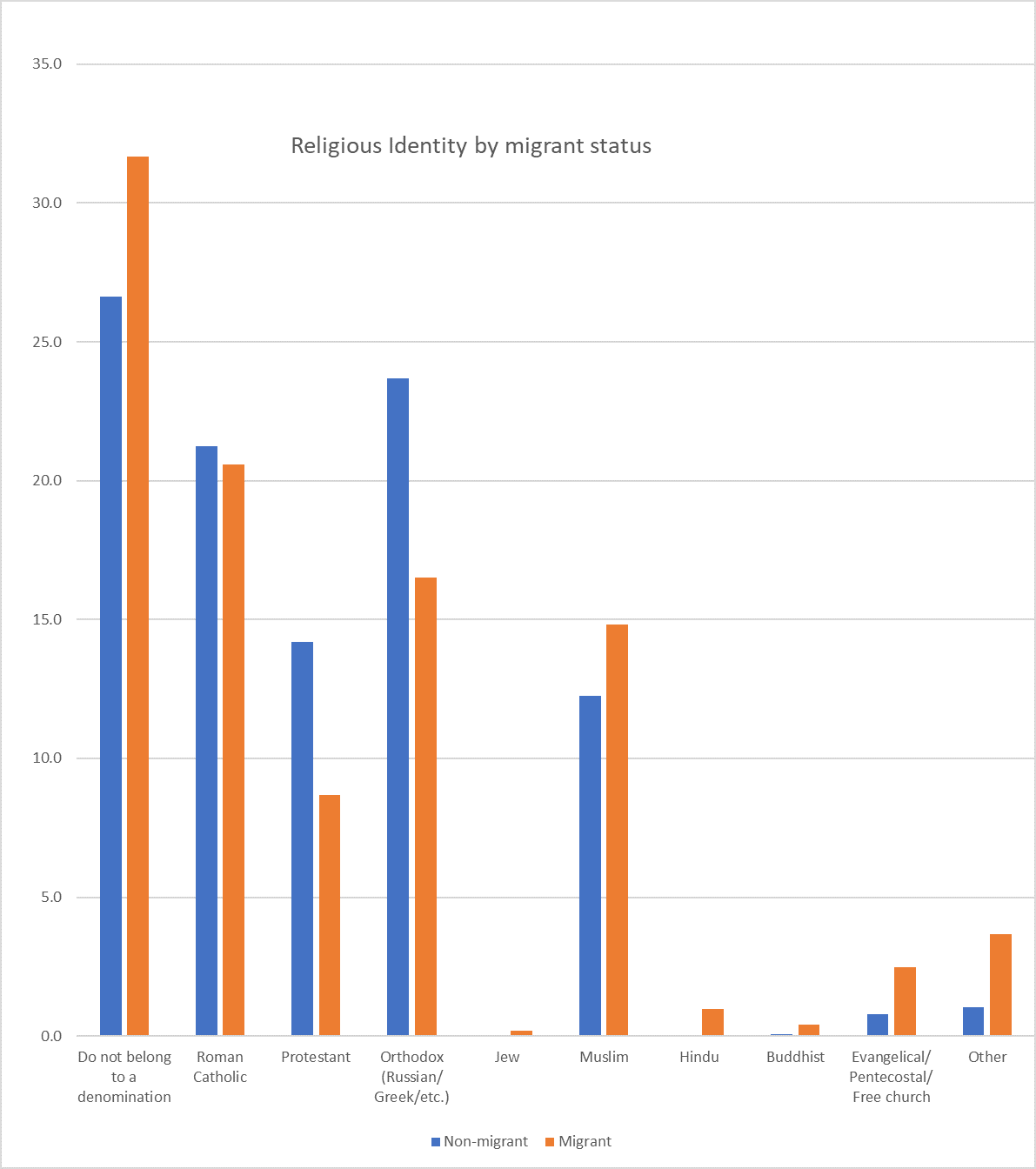

Another note of caution in interpreting these survey results is that they are ‘raw’ numbers. Survey researchers often ‘weigh’ their raw data to adjust for under-representation of certain type of people (including migrants who might be less inclined to respond, less easily located, or who struggle to communicate in the language of the research team). For this reason, where we compare the responses of migrants and non-migrants, we show our data as a percentage of each of these two categories of respondents. Where we report that 26.6% of non-migrants say they do not belong to any religious denomination, the figure of 26.6% is telling us that just over a quarter of all non-migrants who answered this question do not belong to a religious denomination.

The EVS/WVS 2017 Survey asked respondents to indicate whether they ‘belonged’ to a religious denomination or tradition. If they indicated they did ‘belong’, they were asked to indicate which one this was. In some countries, there were options to indicate Sunni or Shia Muslim, for example. The data is collated by EVS into broad denominational streams – the streaming used is highly likely to match the interest to readers of VISTA.

We can present this data graphically, as follows

Of course, saying that you ‘belong’ to a denomination is not necessarily a guarantee of regular attendance nor is it evidence of personal faith. However, what is of particular interest is that religious belonging is expressed by slightly fewer migrants (68.3%) than it is by non-migrants (73.4%). However, migrants are more likely to belong to either a Muslim community or to be evangelical/Pentecostal/Free church than are the non-migrants who were surveyed. This points to the ongoing need for evangelical churches across Europe to continue wrestling with the realities of migrant Christian faith and taking careful stock of what it means to minister to Muslim migrants in the name of Jesus and with compassion.

When attendance at a religious service is measured, over and above a sense of ‘belonging’ to a religious denomination or tradition, the following table begins to show some very interesting patterns. Whilst claims to ‘belong’ to a denomination might be made less frequently by migrants than by non-migrants, the likelihood is that migrants are more likely than non-migrants to be regular attenders at weekly, or more than weekly, services. This suggests that claims of religious belonging are a way of non-migrants saying something about their cultural identity that does not necessarily translate into regular service attendance.

Of course, we need to be cautious about regular service attendance being a sign of genuine personal faith. Migrants might attend a church service or Friday prayers because they appreciate the community, relationship, hospitality, and the support that these are at a merely human level. These, of course, are not uncommonly offered by churches across Europe as an expression of Christian mission, of a love for God and neighbour.

What evidence might we draw from survey responses to questions about the practice of private prayer. EVS has asked a variety of questions about personal religious practices over the past few decades and the practice of private prayer continues to offer some of the strongest evidence for a personal, or owned, religious identity. What the table opposite shows is that migrants are more likely to pray privately on a daily basis and slightly less likely to say that they never pray.

When the practice of private prayer is correlated with religious belonging, migrants who belong to the Roman Catholic, Protestant, or Free church/ Pentecostal/ Evangelical churches are more likely to pray every day than do non-migrants who belong to these denominations or traditions. Interestingly the same is also true for Muslim migrants than it is for Muslim non-migrants. This data is presented below:

Finally, we present here the EVS data that asks the very simple question about personal belief in God. On this measure, migrants are move convinced of the existence of God than are non-migrants.

Our initial presentation of data from the 2017 round of the EVS and WVS surveys suggests that migrants are generally more regular and more fervent in their religious affiliation, religious practice, and religious beliefs than are their non- migrant co-religionists. Of course, the EVS data is far from perfect and there are many careful qualifications that must be made in order to offer a more sophisticated picture of the trends regarding migrant religiosity. Nevertheless, readers of VISTA can be grateful that across Europe, the EVS data shines a light upon the presence and practices of migrants in Europe’s places of worship and houses of prayer.

Associate Professor Darrell Jackson, Whitley College, University of Divinity. djackson@whitley.edu.au

End notes

Readers interested in exploring data at national level, along with other relevant migrant data, are invited to consider purchasing a copy of the 3rd Mapping Migration in Europe, Mapping Churches’ responses: Being Church Together (2020) written by Darrell Jackson and Alessia Passarelli. Almost 100 pages of infographics present their migration data in new and fascinating ways.